Though some gardeners may be blessed with perfect soil, most of us garden in soil that is less than perfect. If your soil has too much clay in it, is too sandy, too stony or too acidic, don't despair. Turning a poor soil into a plant-friendly soil is not difficult to do, once you understand the components of a healthy soil.

Soil is composed of weathered rock and organic matter, water and air. But the hidden "magic" in a healthy soil is the organisms—small animals, worms, insects and microbes—that flourish when the other soil elements are in balance.

Minerals. Roughly half of the soil in your garden consists of small bits of weathered rock that has gradually been broken down by the forces of wind, rain, freezing and thawing and other chemical and biological processes.

Soil type is generally classified by the size of these inorganic soil particles: sand (large particles), silt (medium-sized particles) or clay (very small particles). The proportion of sand, silt and clay particles determines the texture of your soil and affects drainage and nutrient availability, which in turn influence how well your plants will grow.

Organic Matter. Organic matter is the partially decomposed remains of soil organisms and plant life including lichens and mosses, grasses and leaves, trees, and all other kinds of vegetative matter.

Although it only makes up a small fraction of the soil (normally 5 to 10 percent), organic matter is absolutely essential. It binds together soil particles into porous crumbs or granules which allow air and water to move through the soil. Organic matter also retains moisture (humus holds up to 90 percent of its weight in water), and is able to absorb and store nutrients. Most importantly, organic matter is food for microorganisms and other forms of soil life.

You can increase the amount of organic matter in your soil by adding compost, aged animal manures, green manures (cover crops), mulches or peat moss. Because most soil life and plant roots are located in the top 6 inches of soil, concentrate on this upper layer. To learn more about making your own compost. Be cautious about incorporating large amounts of high-carbon material (straw, leaves, wood chips and sawdust). Soil microorganisms will consume a lot of nitrogen in their efforts to digest these materials and they may deprive your plants of nitrogen in the short run.

Soil life. Soil organisms include the bacteria and fungi, protozoa and nematodes, mites, springtails, earthworms and other tiny creatures found in healthy soil. These organisms are essential for plant growth. They help convert organic matter and soil minerals into the vitamins, hormones, disease-suppressing compounds and nutrients that plants need to grow.

Their excretions also help to bind soil particles into the small aggregates that make a soil loose and crumbly. As a gardener, your job is to create the ideal conditions for these soil organisms to do their work. This means providing them with an abundant source of food (the carbohydrates in organic matter), oxygen (present in a well-aerated soil), and water (an adequate but not excessive amount).

Air

Air. A healthy soil is about 25 percent air. Insects microbes, earthworms and soil life require this much air to live. The air in soil is also an important source of the atmospheric nitrogen that is utilized by plants.

Well-aerated soil has plenty of pore space between the soil particles or crumbs. Fine soil particles (clay or silt) have tiny spaces between them - in some cases too small for air to penetrate. Soil composed of large particles, like sand, has large pore spaces and contains plenty of air. But, too much air can cause organic matter to decompose too quickly. To ensure that there is a balanced supply of air in your soil, add plenty of organic matter, avoid stepping in the growing beds or compacting the soil with heavy equipment and never work the soil when it is very wet.

Water. A healthy soil will also contain about 25 percent water. Water, like air, is held in the pore spaces between soil particles. Large pore spaces allow rain and irrigation water to move down to the root zone and into the subsoil. In sandy soils, the spaces between the soil particles are so large that gravity causes water to drain down and out very quickly. That's why sandy soils dry out so fast.

Small pore spaces permit water to migrate back upwards through the process of capillary action. In waterlogged soils, water has completely filled the pore spaces, forcing out all the air. This suffocates soil organisms as well as plant roots.

Ideally, your soil should have a combination of large and small pore spaces. Again, organic matter is the key, because it encourages the formation of aggregate, or crumbs, or soil. Organic matter also absorbs water and retains it until it is needed by plant roots. Every soil has a different combination of these five basic components. By balancing them you can dramatically improve your soil's healthy and your garden's productivity. But first, you need to know what kind of soil you have.

Soil Texture and Type

Soil texture can range from very fine particles to coarse and gravelly. You don't have to be a scientist to determine the texture of the soil in your garden. To get a rough idea, simply place some soil in the palm of your hand and wet it slightly, then run the mixture between your fingers. If it feels gritty, your soil is sandy; if it feels smooth, like moist talcum powder, your soil is silty; if it feels harsh when dry, sticky or slippery when wet, or rubbery when moist, it is high in clay.

Every soil has unique physical characteristics, which are determined by how it was formed. The silty soil found in an old floodplain is inherently different from stony mountain soil; the clay soil that lay under a glacier for millions of years is unlike the sandy soil near an ocean. Some of these basic qualities can be improved with proper management - or made worse by abuse.

Identifying your soil type: Soils are generally described according to the predominant type of soil particle present: sand, silt or clay. By conducting a simple soil test, you can easily see what kind of soil you're dealing with. You may want to repeat this test with several different soil samples from your lawn and garden.

- Fill a quart jar about one-third full with topsoil and add water until the jar is almost full.

- Screw on the lid and shake the mixture vigorously, until all the clumps of soil have dissolved.

- Now set the jar on a windowsill and watch as the larger particles begin to sink to the bottom.

- In a minute or two the sand portion of the soil will have settled to the bottom of the jar. Mark the level of sand on the side of the jar.

- Leave the jar undisturbed for several hours. The finer silt particles will gradually settle onto the sand. You will find the layers are slightly different colors, indicating various types of particles.

- Leave the jar overnight. The next layer above the silt will be clay. Mark the thickness of that layer. On top of the clay will be a thin layer of organic matter. Some of this organic matter may still be floating in the water. In fact, the jar should be murky and full of floating organic sediments. If not, you probably need to add organic matter to improve the soil's fertility and structure.

Improving Soil Structure

Even very poor soil can be dramatically improved, and your efforts will be well rewarded. With their roots in healthy soil, your plants will be more vigorous and more productive.

Sandy Soil. Sand particles are large, irregularly shaped bits of rock. In a sandy soil, large air spaces between the sand particles allow water to drain very quickly. Nutrients tend to drain away with the water, often before plants have a chance to absorb them. For this reason, sandy soils are usually nutrient-poor.

A sandy soil also has so much air in it that microbes consume organic matter very quickly. Because sandy soils usually contain very little clay or organic matter, they don't have much of a crumb structure. The soil particles don't stick together, even when they're wet.

To improve sandy soil:

- Work in 3 to 4 inches of organic matter such as well-rotted manure or finished compost.

- Mulch around your plants with leaves, wood chips, bark, hay or straw. Mulch retains moisture and cools the soil.

- Add at least 2 inches of organic matter each year.

- Grow cover crops or green manures.

Clay Soil. Clay particles are small and flat. They tend to pack together so tightly that there is hardly any pore space at all. When clay soils are wet, they are sticky and practically unworkable. They drain slowly and can stay waterlogged well into the spring. Once they finally dry out, they often become hard and cloddy, and the surface cracks into flat plates.

Lack of pore space means that clay soils are generally low in both organic matter and microbial activity. Plant roots are stunted because it is too hard for them to push their way through the soil. Foot traffic and garden equipment can cause compaction problems. Fortunately, most clay soils are rich in minerals which will become available to your plants once you improve the texture of the soil.

To improve clay soil:

- Work 2 to 3 inches of organic matter into the surface of the soil. Then add at least 1 inch more each year after that.

- Add the organic matter in the fall, if possible.

- Use permanent raised beds to improve drainage and keep foot traffic out of the growing area.

- Minimize tilling and spading.

Silty Soil. Silty soils contain small irregularly shaped particles of weathered rock, which means they are usually quite dense and have relatively small pore spaces and poor drainage. They tend to be more fertile than either sandy or clayey soils.

To improve silty soil:

To improve silty soil:

- Add at least 1 inch of organic matter each year.

- Concentrate on the top few inches of soil to avoid surface crusting.

- Avoid soil compaction by avoiding unnecessary tilling and walking on garden beds.

- Consider constructing raised beds.

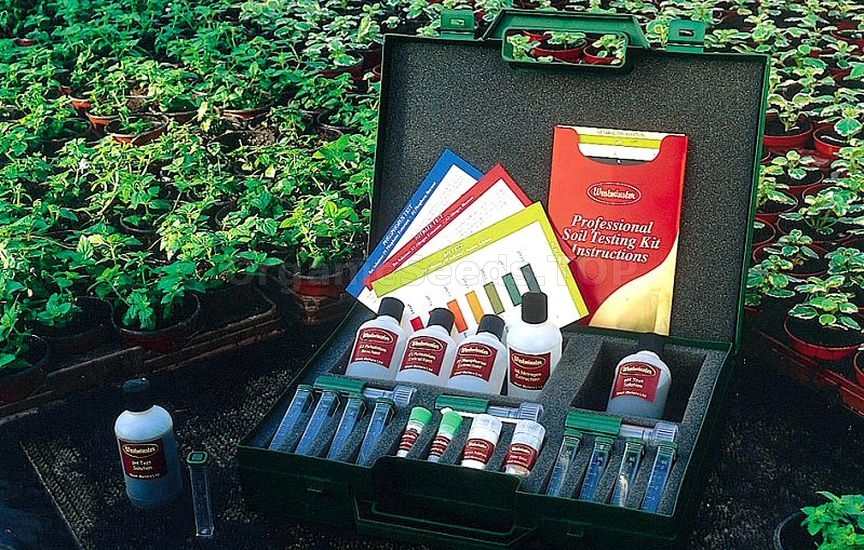

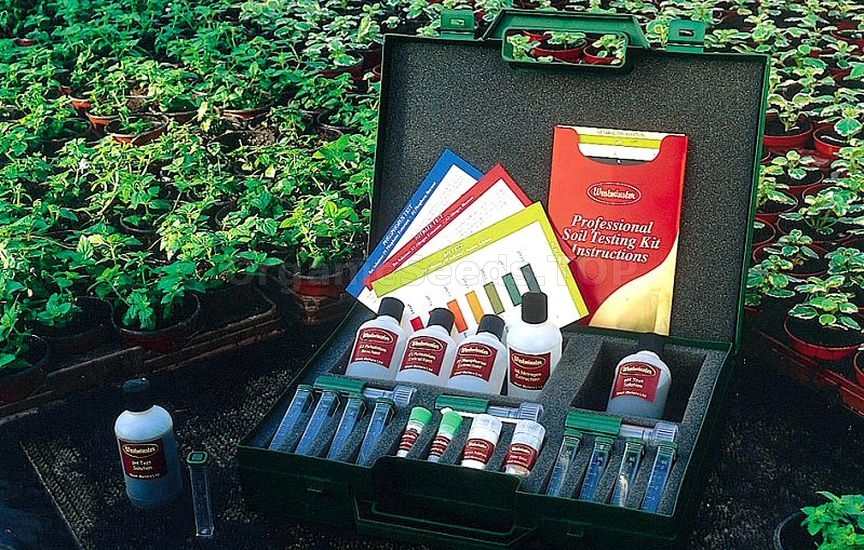

Soil pH

The pH level of your soil indicates its relative acidity or alkalinity. A pH test measures the ratio of hydrogen (positive) ions to hydroxyl (negative) ions in the soil water. When hydrogen and hydroxyl ions are present in equal amounts, the pH is said to be neutral (pH 7). When the hydrogen ions prevail, the soil is acidic (pH 1 to pH 6.5). And when the hydroxyl ions tip the balance, the pH is alkaline (pH 6.8 to pH 14).

Most essential plant nutrients are soluble at pH levels of 6.5 to 6.8, which is why most plants grow best in this range. If the pH of your soil is much higher or lower, soil nutrients start to become chemically bound to the soil particles, which makes them unavailable to your plants. Plant health suffers because the roots are unable to absorb the nutrients they require.

To improve the fertility of your soil, you need to get the pH of your soil within the 6.5 to 6.8 range. You can't, and shouldn't try, to change the pH of your soil overnight. Instead, gradually alter it over one or two growing seasons and then maintain it every year thereafter. Liberal applications of organic matter is a good idea too, because it helps to moderate pH imbalances.

Acidic Soil. If the pH of your soil is less than 6.5, it may be too acidic for most garden plants (although some, such as blueberries and azaleas require acidic soil). Soils in the eastern half of the U.S. are usually on the acidic side.

The most common way to raise the pH of your soil (make it less acidic) is to add powdered limestone. Dolomitic limestone will also add manganese to the soil. Apply it in the fall because it takes several months to alter the pH.

Wood ash will also raise the pH, and it works more quickly than limestone and contains potassium and trace elements. But if you add too much wood ash, you can drastically alter the pH and cause nutrient imbalances. For best results, apply wood ash in the winter, and apply no more than 2 pounds per 100 square feet, every two to three years.

To raise the pH of your soil by about one point:

- In sandy soil: add 3 to 4 pounds of ground limestone per 100 square feet.

- In loam (good garden soil): add 7 to 8 pounds per 100 square feet.

- In heavy clay: add 8 to 10 pounds per 100 square feet.

Alkaline Soil. If your soil is higher than 6.8, you will need to acidify your soil. Soils in the western U.S., especially in arid regions, are typically alkaline. Soil is usually acidified by adding ground sulfur. You can also incorporate naturally acidic organic materials such as conifer needles, sawdust, peat moss and oak leaves.

To lower soil pH by about one point:

To lower soil pH by about one point:

- In sandy soil: add 1 pound ground sulphur per 100 square feet.

- In loam (good garden soil): add 1.5 to 2 pounds per 100 square feet.

- In heavy clay: add 2 pounds per 100 square feet.